Amazon’s Jeff Bezos & microsoft founder Bill Gates chase Dream of a Blood Test That Detects Cancer

If cancer is an unwelcome intruder in the body, it’s also a careless vandal, leaving traces of its presence sprinkled throughout the blood. And if you believe Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, therein lies both a medical revolution and a pot of gold.

Scientists have known for decades that tumors shed bits of DNA that end up in the blood. Now, with advances in genetic sequencing technology, startups are beginning to identify those shreds of DNA with so-called “liquid biopsies,” less invasive, less expensive alternatives to tissue samples that can track tumor mutations in cancer patients.

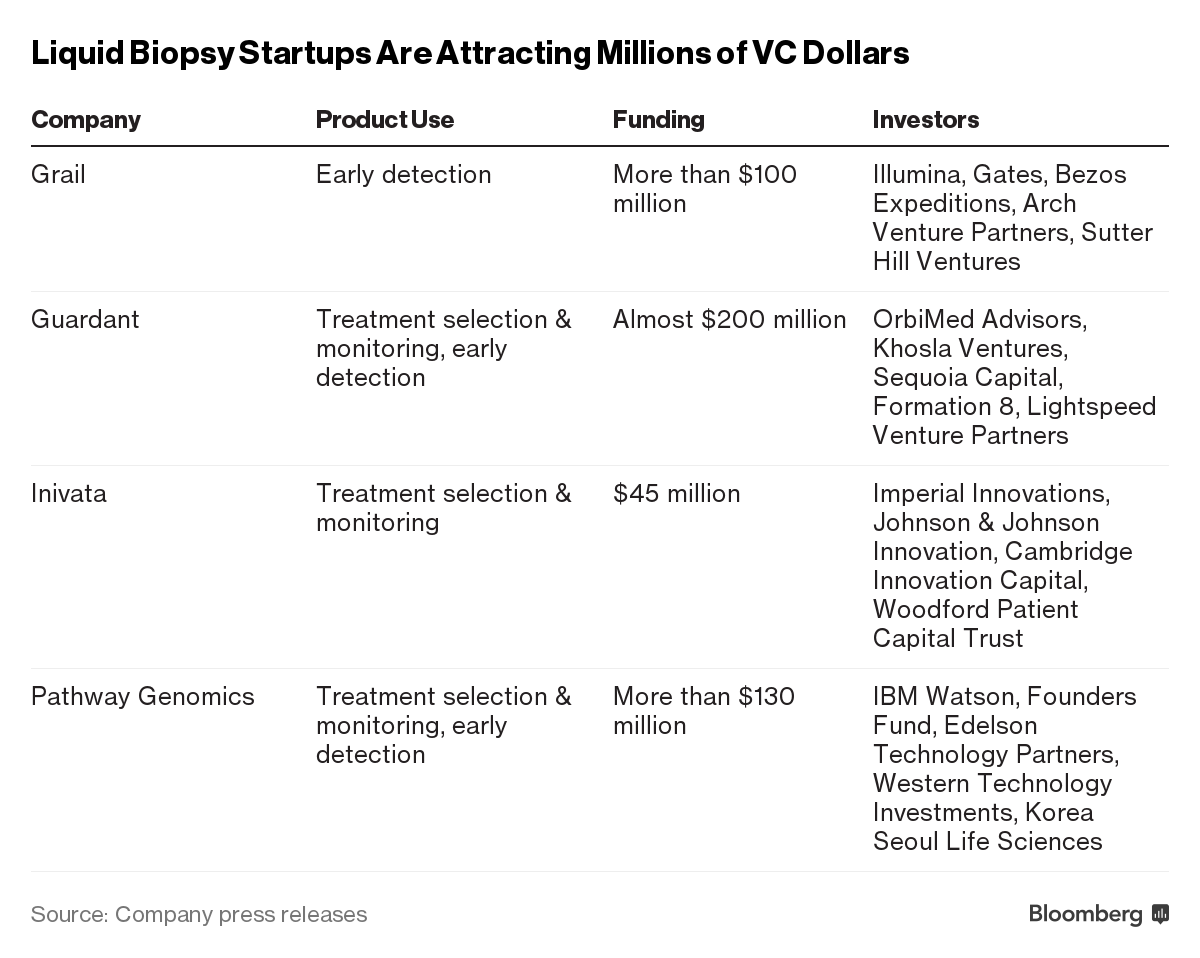

An even bigger prize may be on the horizon: a simple-to-administer yet all-encompassing blood test that would screen for every kind of known cancer in the human body even before a person showed or felt any symptoms. Bezos, Gates and others are investing hundreds of millions of dollars to make such a super-screening test a reality. If they’re successful, the market opportunity may reach $200 billion a year in sales, according to the technology’s boosters.

The push is nothing less than “trying to turn all of oncology on its head,” says Robert Nelsen, co-founder and managing director of Arch Venture Partners, which led the $100 million fundraising round of liquid biopsy startup Grail. “Maybe 10 years from now, when you have cancer you’ll never see a hospital.”

Long Trials

Critics say such talk amounts to hyperbole and minimizes the medical and financial risks that lie ahead. An accurate early-detection blood test is years away and will require successful trials to convince doctors and insurers of the benefits of screening. Anything less than flawless precision could mean misdiagnoses and mistreatment.

“The path will be long until we can make any reasonable claims,’’ says Cyrus Hedvat, director of the molecular pathology laboratory at NYU Langone Medical Center. “That never stopped any company from marketing.”

And even the technology’s most ardent backers realize they may ultimately be chasing a medical goal beyond anyone’s reach.

“Is this dream that one day we’ll have a universal screening test a realizable dream,” says Richard Klausner, a Grail board member. “Or a pipe dream?”

Early Detection

At least 38 companies are developing or already selling some form of liquid biopsy, according to a September report by Piper Jaffray analyst William Quirk. Most, including Guardant Health Inc., Trovagene Inc., Genomic Health Inc. and Foundation Medicine Inc., are working on screening for already-diagnosed patients, to help doctors pick treatments that target specific mutations and watch for recurrence. More ambitious companies are going for very early-stage cancer detection. Many are touting their products as revolutionary, even though tests have yet to be completed.

Grail, founded earlier this year by genetic sequencing machine maker Illumina Inc., has hired Jeff Huber, a longtime Google executive, to head up the company. For Huber, whose wife died in November from colon cancer that was only diagnosed at stage 4, the success of Grail’s screening technology is personal.

Saving Lives

“If it was available 10 years ago, she would be alive today,” he said in an interview in February.

Huber, who declined to be interviewed for this story, referring questions to Klausner, said earlier that the company will aim initially for a $1,000 price per test. “Ultimately we see this as having value for everyone in the world,” he said. “The market is 7.4 billion people.”

Illumina’s CEO Jay Flatley told investors that the market opportunity, if the test is everything it promises to be, would be $100 to $200 billion, and told Bloomberg News that an initial pan-cancer test should be ready by 2019. Illumina has a majority stake in closely held Grail. Others have more modest estimates: Analyst Quirk said in September he thinks the market for all types of liquid biopsies, including screening and monitoring, will be under $30 billion.

Tumor Tissue

The science is advancing and some companies are already bringing preliminary tests to market. When cells in the body die — tens of billions a day in healthy humans — some DNA fragments typically escape into the bloodstream. Rapidly growing cancer cells also leave their mark in the blood. The more advanced the cancer, the more of this “cell-free DNA” tends to be circulating in the blood, making it easier to detect. Closely held Guardant’s test, which retails at $5,800, has been used by almost 20,000 advanced cancer patients to date.

This can help patients who don’t have enough tumor tissue to do a traditional biopsy — some 20 percent to 50 percent of cases, according to Helmy Eltoukhy, Guardant’s chief executive officer. A blood test is an easy way for doctors to monitor patients with rapidly evolving cancers, and also look out for recurrence, said Michael Stocum, CEO of closely held Inivata Ltd., which is developing a monitoring test for lung cancer patients.

Mutant Variants

On the other hand, early screenings for cancer can cause more angst than clarity. That’s because there are many ways that a gene can mutate, and just because DNA may appear abnormal doesn’t necessarily mean it’s pointing to cancer, says Kristen McCaleb, who until recently was program manager for the UCSF Genomic Medicine Initiative. She now works at Invitae Corp. A broad screening test could turn up variants that doctors don’t understand well enough to say with certainty whether they are dangerous or benign.

“Oncologists are going to be inundated with patients freaking out over data that we don’t know what to do with,” she said.

Another problem is that liquid biopsies only can identify incipient cancers’ existence in the body but, so far, researchers can’t figure out where in the body the fragment came from.

A test could “initiate a potentially challenging task to find the source,” said Geoffrey Oxnard, a lung cancer doctor at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “Then you’ll have patients who say, ‘I have cancer and I have no idea where it is.’”

Wary FDA

Understandably, companies have a lot of work to do before they will be able to persuade doctors to administer cancer screening tests, not to mention convince insurers to cover them, all while avoiding running afoul of an increasingly wary U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“We are certainly looking out for any product that we feel is a danger to public health,” said Eric Pahon, a spokesman for the FDA. The agency encourages liquid biopsy companies to contact the agency before bringing a product to market, he said. “The FDA does not want to stand in the way of innovation, we just want it to happen in a safe way.”

It’s already asked one startup to slow down. In September, the FDA sent a letter to Pathway Genomics, saying the company’s cancer detection kit sold to healthy individuals was high-risk, hadn’t been validated by science, and could harm public health because it hadn’t been proven to work accurately.

‘Powerful Telescope’

Pathway says it’s committed to patient safety and is now “working closely with the FDA to resolve questions they have about the test and the data that it provides to clinicians.”

Grail says it’s also proceeding with care. Illumina CEO Flatley has said Grail plans to start large-scale clinical studies by 2017, before bringing a test to market.

“With Grail, we’re building this unbelievably powerful telescope to allow us, for the first time ever, to ask the questions about what the origin of cancer looks like in the human,” said board member Klausner. “We go into this with an incredible sense of responsibility to do this right.”